Pictures from Winsen with the Camera Obscura

Speech on the occasion of the vernissage by Mathias Riemann

I would like to welcome Przemek Zajfert to the exhibition in the rooms of the Winser Kulturcafé next door. Mr Zajfert, who lives in Stuttgart and is a photographer by trade like his grandfather, was the initiator of this exhibition, the pictures of which were ultimately created by very different and diverse people. 16 photos here in this section from Winsen, the small and medium formats from Munich, Poland, England —who knows, maybe you will discover another place! And then the more or less black and white photographs, more chamois! and sepia by Przemek Zajfert himself – photographic works from 10 years ago from the tranquil little university town of Tübingen, barely 30 kilometres south of his home in Stuttgart.

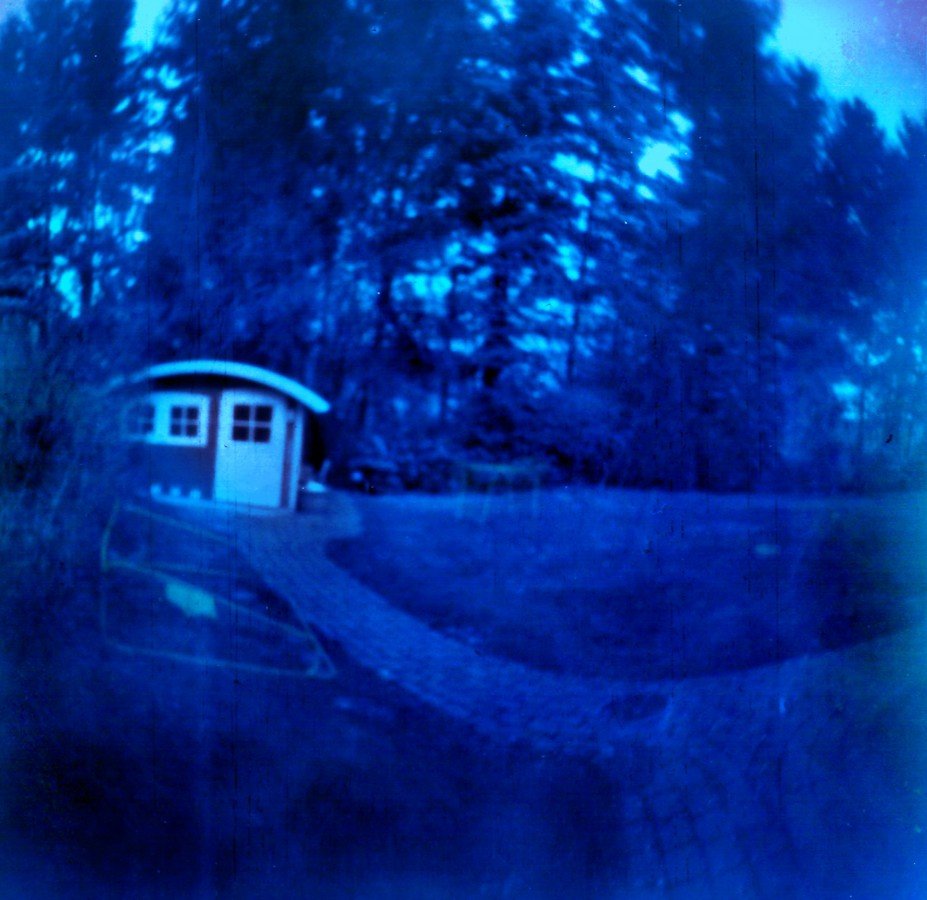

What they all have in common is that they were taken with the oldest photographic technique in the world, a pinhole camera. The pinhole camera is the distinctive mark of the artist, who has tried out various pinhole cameras – they differ in the variation of box and exposure time. The latter in turn depends on the photographic material used. On one side is the incidence hole for the light, on the other side of the small black box the photosensitive material, which is exposed for 3 minutes, 2 hours, one or even 7 days, or even 14 days, depending on its nature. The photographs from Tübingen have much shorter exposure times – 2 hours – than the small 4×5 or 5×7 film formats that fit into a film box, for example, as the older ones among us still know them from the times of chemical photography when Agfa, Kodak or Ilford sold their films in these film boxes. These film formats can withstand exposure times of 7 days to even a year!

A box is created, with a tiny opening that corresponds to about aperture 180, bent in the film canister, which comes close to a wide angle of about 120 degrees. The whole thing is not just a whim, a product of chance on a whim to earn a little money at an adventurous Christmas market. Just as it is not a coincidence what comes out of the design. There is a very fundamental consideration behind it – because in every – especially increasingly complex – technical orientation, as we experience it in photography, there is a limitation within the technical programme. The photographer moves within the limits imposed by the technique. If, on the other hand, Przemek Zajfert avoids this technique or reduces it to a minimum, he gains the greatest possible artistic freedom.

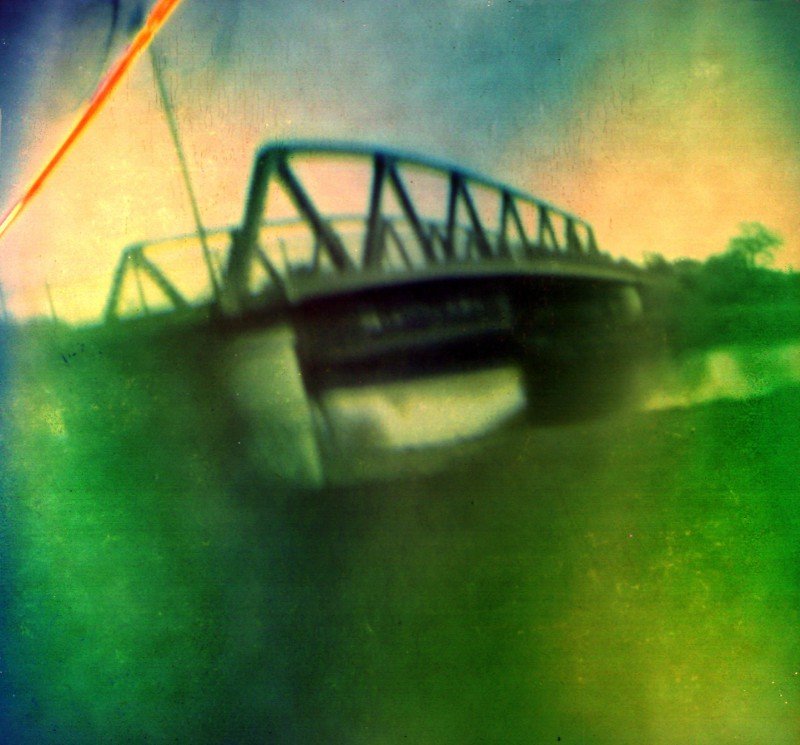

Przemek Zajfert has now sold over 5000 of these film can cameras worldwide – in Winsen, as I said, 16 of these small cameras obscura were used – church and bridge, shed and abstract reflection, the house opposite, the church street, a piece of playground equipment, the familiar view out of the window – familiar and less familiar motifs can be found.

What they have in common is that their authors have taken time, time to consider, where do I put the photo box? Time for the light to fall into it. Przemek Zajfert called this project The 7th Day, seven days, or the seventh day. But on the seventh day God rested from all his works which he had made and created. This is how heaven and earth became when they were created.

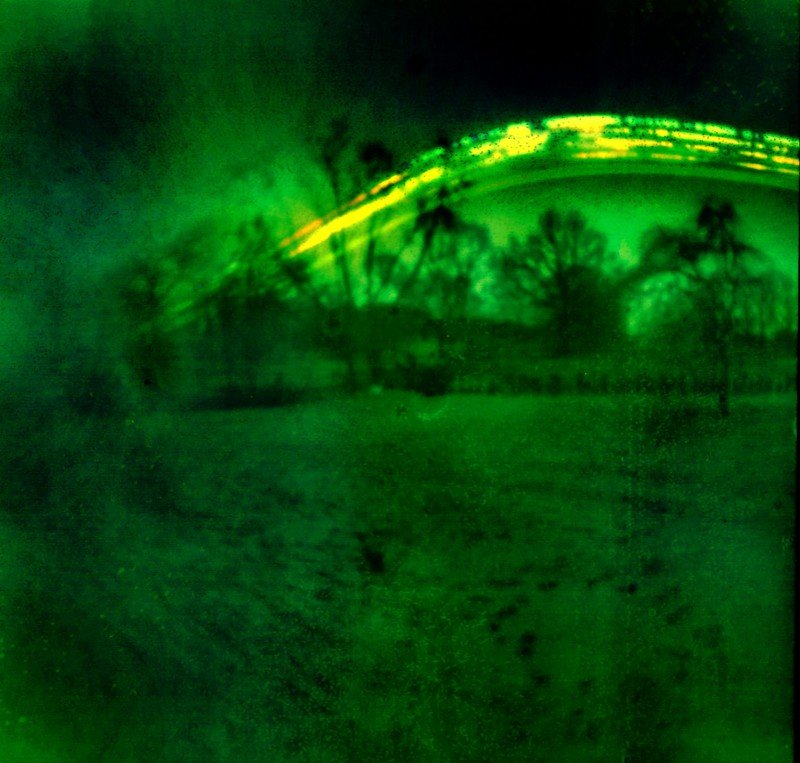

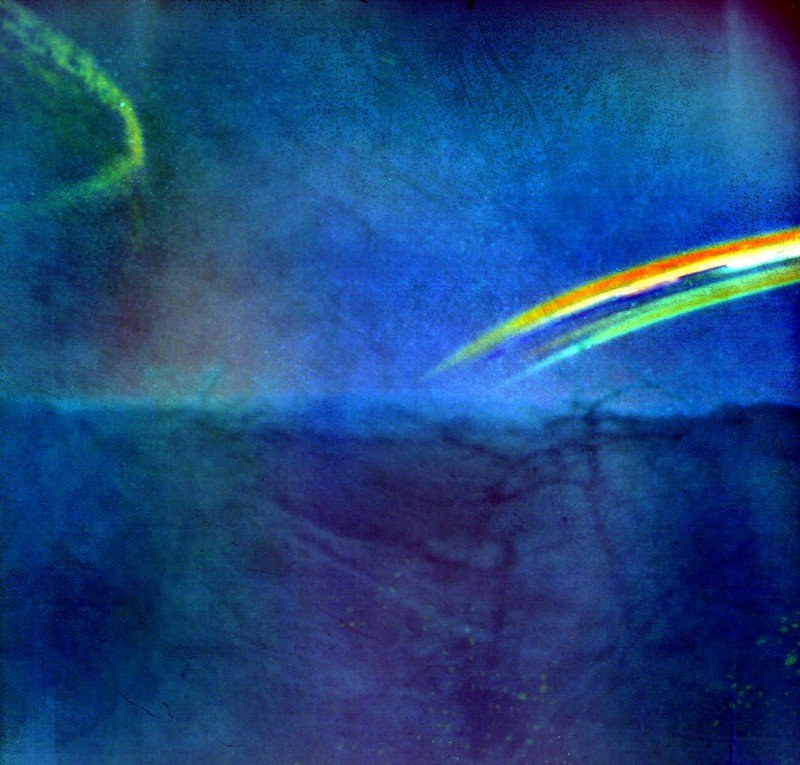

The number 7 provides a rhythm, it describes an arc, because it aims at completion, at what has been created, at what is finished. It is a directed number. It sets itself apart from the constant activity, the multiformity, the permanent hectic movement. What I find most exciting about the pictures in this project is that they do capture movement – but not the flight of a bird, the tininess of a moment when a car drives by – no, the photos as a whole seem as if they were in motion, in other words: exposed to a creative movement from which they have been brought to rest. The edges do not remain sharply drawn and the colours seem painted, watercoloured. Looking at them triggers a pleasant reflex – I think to myself, my eye thanks me for not having to focus all the time. The digital world, after all, is a world that forces my eye to constantly flit behind the multitude of small data points – the razor-sharp image is actually an optical illusion, since it gains this sharpness from an imaging process that aims to maximise the fading out of the speed at which the individual particles move back and forth.

In short: the photos of the camera obscura interpret time, they deal with time, with transience.

The long exposure time achieves two additional effects that are related to the basic theme of time in a further arc. On the one hand, the course of the sun is traced in many of the photos. You can see from the photos whether the camera was pointed towards the east, when the sun is slowly rising, or towards the west, when it is falling. You can see in the photos the movement of the earth when a slightly higher strip of the sun has been imaged the next day – in winter and spring these strips are closer together, in summer they pull further apart. Despite the sun and daylight, the pictures, at least the pictures exposed for 7 days, are without shadows. This is probably why they seem magical in a certain way, undefined. The shadow represents the side that is turned away from the light, thus the shadow stands for the dark sides, for the shadow of the murderer in the films of Orson Welles. The photos appear as if they were taken in the middle of the night and artificially brightened, as if at dawn, when the light does not yet have the power to illuminate parts of the picture in order to put other parts in shadow. I.e., the long exposure time of the camera obscura skips, so to speak, day after day, the power of the sun to illuminate one thing and put another to the side. What remains is the sum of all this. The shadow, like the sun, moves across the picture and gives the photo its blur of movement, its magic. In the story of creation, the seventh day marks the day of rest, in other words: the completion of creation. But is creation really finished? The philosopher Ernst Bloch says: we are, but we have not yet. For me, the photos shown here capture this moment, so to speak – yes, the created is there, it has come into the world, it is there – but we are still waiting to have ourselves in it, to see ourselves again and again, to invent ourselves, to have ourselves, within the limits of light and shadow. Ernst Bloch had the habit of reflecting on this and other philosophical questions in the armchair he used for his lectures in the Gastl bookshop. Przemek Zajfert has a picture of this object of desire – I studied in Tübingen, I can tell – it hangs in the small Tübingen row in the next room. There you can also see a photo of Walter Jens, another local Tübingen great who achieved literary fame. Walter Jens in his armchair in his study – two hours, sometimes he stood up, sometimes he moved, sometimes he stayed seated – his body like a ghost flitting across the picture; an almost prophetic photo, if you consider how Walter Jens’ life slowly took its leave of the earth in the aftermath.

With this note, I conclude the introduction to this exhibition, which I am very pleased to have brought about, and declare it open. Take a look around the rooms and then come outside – music is waiting outside and then the lecture by Hans-Martin Heinemann from Hanover.